Ethical Horizons and Legal Frameworks for Colonial Collections

Report on the Pressing Matter Consortium Meeting, 13 December 2024, Wereldmuseum-Leiden, by Ana Rita Amaral

The latest bi-annual meeting of the Pressing Matter Project Consortium marked the end of a series of thematic events designed to bring together the project’s researchers with its critical friends and various academics to discuss key concepts, issues and approaches that guide our work on colonial heritage in museums. This time, the focus was on the intersection of the legal and the ethical, not only in the context of research but also and especially of restitution.

The day was divided into two parts – a morning of presentations and discussions on heritage law and ethics, and after lunch a session on codes of conduct and research integrity, followed by a presentation and reflection on what happens after restitution. All speakers and participants sought to address questions such as: How can legal and ethical frameworks be critically engaged to address historical injustices without perpetuating colonial biases? What limiting and inspiring challenges do they pose for researchers and museum practitioners working with collections acquired in colonial contexts? What role do museums – and museum-based research – play in critically reshaping not only these legal and ethical frameworks, but also the narratives about restitution and, more broadly, about our entangled (legal) pasts, presents and futures?

The video recordings of the event are available here, so rather than summarise each intervention, in this report I will highlight some of the key concepts and themes, as well as interesting approaches and questions that emerged throughout the day.

Among the themes that most speakers sought to unpack were the complicity of the law in colonial exploitation and the need to interrogate the colonial foundations of legal norms and its continuing effects in the present. The principle of the intertemporality of the law – encapsulated in the phrase “it was the law at the time”, often heard in debates about past injustices and ways to redress them – emerged as one of the most problematic and worthy of attention by legal and museum scholars and practitioners, particularly those working on restitution. Its rationale lies in the notion that actions should be judged on the basis of the laws in force at the time of the events, as Marie-Sophie de Clippele explained, but there are significant exceptions when it comes to cultural heritage, and critical interpretations should question not only possible historical legal vacuums, but also the (colonial) foundations of the law itself. De Clippele cited the Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL) to affirm that legality at the time may itself be inherently flawed and therefore in need of critique.

The interplay between the law and ethics was undoubtedly the overarching theme of the day, with Wouter Veraart arguing more explicitly for the role of law in addressing the legacies of colonial injustice. While ethics is an important and necessary foundation, as all speakers seemed to agree, for Veraart ethics is insufficient without enforceable legal mechanisms to consolidate and operationalise restitution. In other words, legal mechanisms have the potential to reinforce ethical imperatives and recalibrate power dynamics. In turn, this ability of the law to come to the aid of those who have been, and continue to be, racialised – or “raced”, another word that was used – by that very law was questioned by some speakers.

In his discussion of punitive expeditions and “Kings in boxes”, i.e., the simultaneous double exile of various African and Asian kings and their regalia at the time of military colonial occupations, Veraart also highlighted how such looting was intertwined with acts of material and symbolical subjugation. To better approach this, he brought to the table the notion of “dignity takings”, first outlined by Bernardette Atuahene – who was recently a guest on the “Otherwise Property Conversations” series. This term has the potential to better evoke the idea that colonial looting was more than the taking of objects – it was deeply connected to acts of dehumanisation and subjugation.

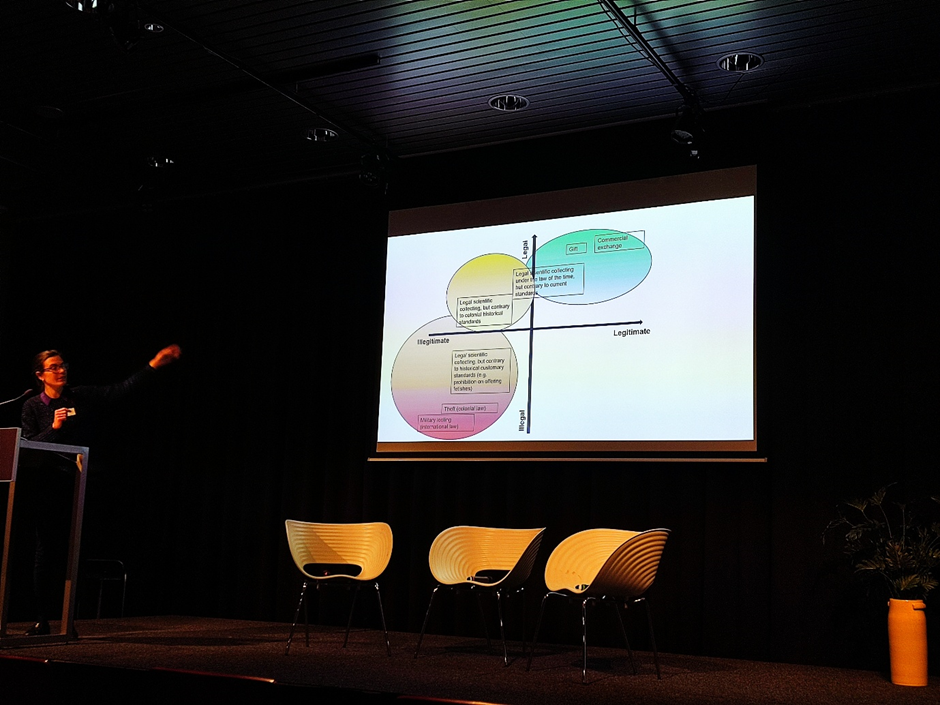

The question of legitimacy was pertinently raised by Marie-Sophie de Clippele, who suggested a gradualist approach to examining acquisition or collection practices for restitution purposes. The issue is itself contained in the Dutch word “roofkunst”, which seems to encompass both the notion of illegal and illegitimate. The important consideration here is that when thinking about the two pairs legality/legitimacy and illegality/illegitimacy, two paths open up – claims for redress and restitution can follow either a legal path focusing on illegality, or an ethical or political path focusing on illegitimacy. The two are intertwined, but while a judge may prioritise legal claims, ethical considerations, including those on the moral duty to redress past injustices, are central in non-judicial mechanisms, as seen in the Sarr-Savoy report (with its lawyerly language, as Veraart pointed out) or in bilateral agreements.

Marie-Sophie de Clippele explaining the (il)legal-(il)legitimate grid.

An interesting grid to assess cases along a spectrum of legality and legitimacy was proposed by De Clippele, where on one extreme corner would be the clear-cut cases like war booty (illegal and illegitimate) and on the other corner would be more ambiguous cases of scientific collecting (legal but potentially illegitimate by today’s standards) and gifts. This grid was the topic of interesting discussions over lunch, at least those I participated in, namely about missionary collecting and the notion of gift – what circumstances shape the gift and its interpretation? What about forms of collective ownership, what do they imply in gift economies?

The need for pluralistic legal approaches was also mentioned, as well as the question of “customary law” and how to integrate local legal and ethical principles alongside international and Western (colonial) legal considerations.

Restitution claims in relation to sacred cultural heritage were addressed by Christa Roodt, who challenged the division between the legal and the ethical and introduced the notion of the “sacred” into the discussion. Are formalistic legal arguments capable of accommodating the intangible, sacred dimensions of cultural heritage? For Roodt, a focus on the sacred – understood here as a property of heritagised items – “can draw our attention to new legal thinking”, as Birgit Meyer framed it in the discussions. The suggestion is that it allows for a methodological innovation, which seems to consist in integrating values that are intrinsic to indigenous worldviews, such as those relating to the sacred and the intangible, into a more comprehensive approach to restitution.

On the question of value, I think two comments are worth highlighting. The first was precisely Roodt’s argument that indigenous valuations of items that have become heritage are “axiomatic”, self-evident or do not need to be demonstrated (for restitution purposes). This seems to be the same idea behind one of the advantages of adopting a legal basis for restitution defended by Veraart. In his words, “we should not burden the objects with the responsibility of their own restitution”. Therefore, debates on restitution should not focus on value but on the circumstances that determined the loss, or the way objects were acquired. This opened interesting discussions over lunch on the question of restitution beyond the “illegal”, i.e. the possibility of restitution claims being based on contemporary processes of revaluation and cultural affirmation on the part of the communities associated with the trajectories of collections today in museums.

The methods and purposes of researching collections, at the heart of Pressing Matter, were continuously discussed throughout the day. The debates on colonial heritage in museums and restitution undoubtedly contributed to bringing a new wave of researchers into museums and to the rise of “provenance research” as a methodology aimed at providing more or less morally and legally satisfactory answers to questions related to how collections were acquired. The need to critically sharpen “provenance research” – for example, by asking: what constitutes the “origin” of an object? – and ensuring its (political and societal) timeliness were raised, while many speakers cautioned against excessive demands for “evidence” and the role of the researcher as an expert, to whom the power to assign value and decide on restitution claims can be ascribed. This burning question was posed by Quinsy Gario in his reflections on the art historian’s craft.

Quinsy Gario at the beginning of his talk “Should we be doing this?”

Gario noted the absence of codes or guidelines in art history as part of his response to Krishma Labib’s presentation on research codes of conduct, their history, purpose, and the challenges they pose to researchers in the humanities. Labib argued that while these codes have their own colonial and Eurocentric biases – the phrase “ethical imperialism” came up –, they can provide pedagogical and aspirational guidelines for acceptable practice. In her perspective, one of the main critical limitations of such codes is that they emphasise issues like autonomy, integrity and transparency to the detriment of justice. The FAIR principles were presented in comparison to the CARE principles, where efforts to address power imbalances and historical inequities seem to be more present.

Finally, the topic of the afterlives of restituted collections was problematised by Sadiah Boonstra, who drew on her involvement in repatriation efforts from the Netherlands to Indonesia. Although Indonesia has a long history of advocating the return of cultural objects, the Netherlands has resisted these demands for decades. Significant progress was made with the creation of government-to-government mechanisms that led to the return of several collections in 2023, which Boonstra described, and their integration into Indonesia’s Museum Nasional.

One of the key questions that emerged was the effectiveness of such restitution efforts in addressing colonial legacies and creating meaningful connections with communities whose histories and cultures are intertwined with those of museum collections. This was a rich session, in which Boonstra shared her thoughts on the risks of politicising restitution and perpetuating colonial frameworks. She also presented the collaborative work she has been doing as part of Pressing Matter on a collection of plaster casts made by a Dutch anthropologist on the island of Nias. Engaging the different communities on the island was a central part of this work, which involved organising an exhibition, entitled Melihat di Balik Wajah Ono Niha (“Looking Behind the Faces”), to encourage dialogue about these collections. The final question she left for discussion was: “What would constitute a good life for restituted objects?”

All the speakers at the final discussion.

The meeting began and ended with reflections by Wayne Modest, Pressing Matter’s Programme Leader and Content Director of the Wereldmuseum. “Who would have thought?”, he asked repeatedly, mentioning several recent milestones in restitution in the Netherlands, namely involving Indonesia, Mexico, and Sri Lanka. The rhetorical question aimed at engaging the audience to share in his surprise and amazement at how far debates questioning the colonial foundations of the law and museum practice seem to have gone in the last fifteen years, overcoming previously prevailing ideas about the legal (“it the law at the time”), conservation (“they can’t take care of it”), agency, and the time and cost of researching heritage.

In sum, by exploring the intersection of ethics and law – the bridging of ethical imperatives with legal accountability to address the enduring legacies of colonialism – the event contributed to problematising the complexities and challenges of restitution, while attempting to set an optimistic tone for the future. As Pressing Matter enters its final phase, the discussions from this and other meetings will undoubtedly inform ongoing debates and practices in the field.